Main information:

Linderhof Park

Abandoned projects in the Linderhof area

Meicost-Ettal

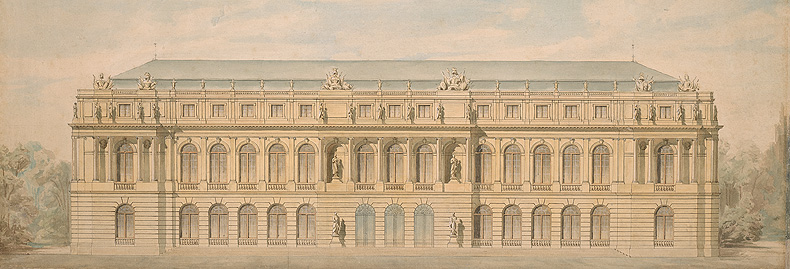

Outline of the garden façade of "Meicost-Ettal":

Project VI, watercolour by Georg Dollmann, 1869

Photo: Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

In 1868 King Ludwig II was already instructing his court architect Georg Dollmann to draw up plans for a new Versailles in the Linderhof valley, which the king named "Meicost-Ettal". Since his early youth, Ludwig II had had a great admiration for the French monarchs, especially Louis XIV: the name "Meicost-Ettal" for the palace that was to be a monument to an absolute monarchy is an anagram of the French Sun King's motto "L 'état c 'ést moi" – "I am the State".

No other palace building was planned with such depth and thoroughness as "Meicost-Ettal", but in 1873 the project was transferred from the Graswangtal to the Herreninsel in the Chiemsee, which the king thought more suitable. From December 1868 to September 1873, seventeen different ground plans were drawn up, together with numerous sketches and many versions of the bedroom.

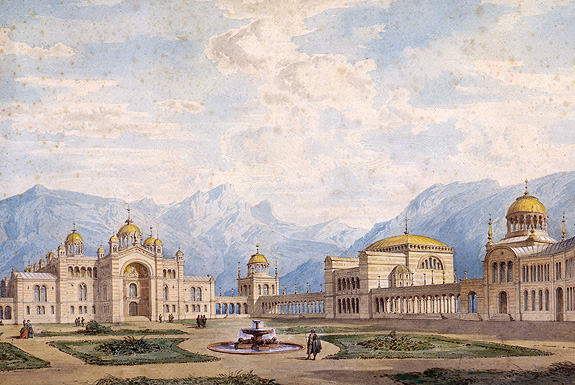

First Byzantine palace project,

watercolour by Georg Dollmann, 1869

Photo: Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, Lucinde Weiss

Byzantine Palace

In 1869, right at the beginning of the Linderhof development, and again in 1885 towards the end of his life, Ludwig II initiated the construction of a Byzantine palace. The first such project was designed from 1869 to 1870 by Georg Dollmann in five different planning stages. The building costs were also calculated, and came to a sum of around 4,300,000 guilders.

For unknown reasons the project was dropped, but the king took it up again in 1885 and a second Byzantine palace was designed by Julius Hofmann, who had succeeded Georg Dollmann as the court architect in 1884. It is as if the king, who was deeply in debt, was trying to create a last refuge to withdraw to.

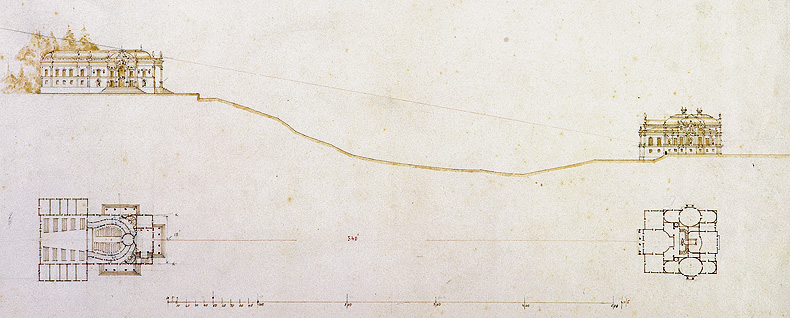

Theatre on the Linderbichl

Sketch and ground plan of Linderhof Palace and the

projected

theatre building on the Linderbichl opposite,

pen-and-ink drawing by Georg Dollmann, 1874

Photo: Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

Ever since King Ludwig II had been taken to see a performance at the Court Theatre with his father as a young crown prince, his passion for the contemporary but nevertheless unreal world of the stage had been growing. The theatre was the most important thing in his life next to his architectural projects, to which it was not unrelated.

Ludwig II used the theatre like a prince of the Renaissance and baroque ages, but he never let himself be influenced by the sets, and he always appreciated the stage and the building itself as two different things. After several projects in different places close to and behind the palace, in 1874 the Linderbichl, the slope opposite the palace, was designated as the location of the theatre. However, for cost reasons it was then decided to build the Temple of Venus here instead. After several more detailed drafts the project was finally abandoned in 1878 when the royal finances were in serious difficulty for the first time.

Project for a chapel in Linderhof Park, watercolour, Georg v. Dollmann, 1875

© WAF, Munich; photo: Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung / Rainer Herrmann

St Anna Chapel

The interior of the chapel built by Ettal monastery in 1684 was redesigned by Ludwig II in 1870/71. Soon after the completion of Linderhof, however, the chapel looked out of place with its simple exterior next to the elaborately designed palace and the king decided to replace it with an appropriate new building.

The first plan for a neo-baroque domed church was soon dropped again. It was probably at the latest in 1876, when the park was taking on its final form, that the king decided to keep the old chapel, and it remained as one of the naive architectural features typical of an English landscape garden.

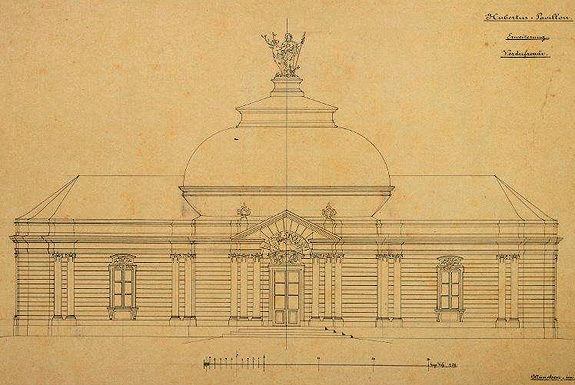

Hubertus Pavilion, pen and ink drawing by Julius Hofmann, 1885

Photo: Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

Hubertus pavilion

While the bedroom was being extended, the king also commissioned a pavilion based on the Amalienburg in the Nymphenburg Palace Park, which was to be sited in the Ammerwald.

Several new starts were made on the walls and foundations to incorporate changes requested by the king, so that by the deadline of October 1885 it was still not complete.

After Ludwig II's death the brick shell was sold, and the furnishings that had already been made or purchased were auctioned.

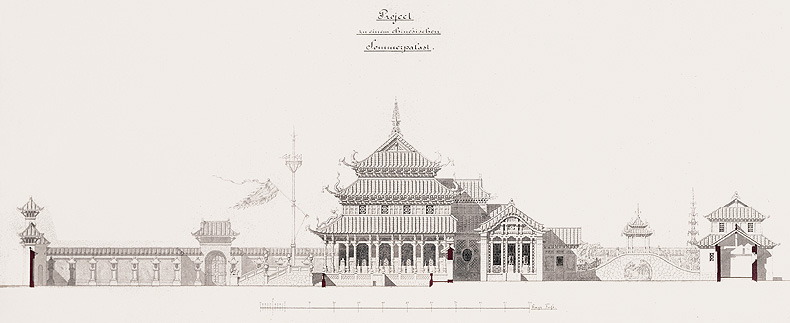

Chinese Summer Palace

Chinese Summer Palace project: Sketch of the

envisaged complex,

pen-and-ink drawing by

Julius Hofmann, 1886

Photo: Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

The king's last project was a Chinese Palace designed for him by Julius Hofmann at the beginning of January 1886. It was partly modelled on the imperial summer palace Yuen-Ming-Yuen, which was destroyed by English troops in 1860; well-known from numerous illustrations, this building had already influenced the fashions of the 18th century. Here too, the king wanted to create the illusion of absolute rule.

The building, of relatively modest proportions, was to be located in the nearby Ammerwald, adding to the various structures sited within reach of the palace such as the Moorish Kiosk, Venus Grotto and Moroccan House. The project, for which the king's last court secretary had already purchased vast quantities of textiles, vases and vessels etc., ceased with the death of the king.

Facebook Instagram YouTube